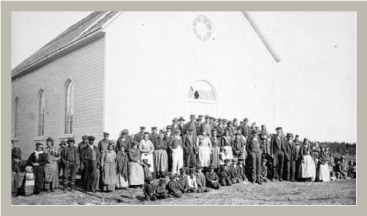

Jesuit missionaries (Father Labrosse in 1769) were present among the “Montagnais” as far as Musquaro (Mahkuanut) on the Lower North Shore. The oblates settled in Unamen Shipu in 1844 and visited the chapels erected next to the HBC trading posts, including Musquaro, where every summer the Montagnais (Innu) families lived. In 1844, Oblate Father Fisette met twenty Montagnais families in Musquaro, which were composed of 46 adults and 37 children. In 1853, this chapel was moved from Musquaro to the Etamamiu site to accommodate both Montagnais and Canadians (French speakers). In 1859, the HBC abandoned its Musquaro site. A new chapel was built in the 1870s in Musquaro with an increasing number of Montagnais families present in the summer (e.g., 100 families in 1906). A Catholic mission remained there until 1946. The French had established a fortified trading post in 1710. The Catholic mission was officially founded in 1800 and the first chapel, in 1805. The Canadian government recently designated the annual missions of the Innu to Musquaro as an event of national significance as part of the 150th anniversary of Canadian confederation.

The Innu arrived in late spring along the coast at the Unamen Shipu trading post, went to Musquaro for the religious mission, joining the Innu of Nastashkuan, Pukuashipu and Kuekuantshit, and then returned to the forest, mainly by the Coucoutchou River, which was an easy way of penetrating into the interior. . .

The increased presence of white fishermen after the end of the monopolies and the leasing of the salmon rivers to wealthy foreigners by the Quebec and Ottawa governments put a legal end to the Montagnais’ traditional salmon fishing activities by the end of the 1850s.

This history primarily discusses the coast because the “Canadian” knowledge of the new residents, traders and missionaries mainly concerned the coastline and not inland. Yet the Innu primarily lived deep in the forest throughout the territory that includes areas other than Unamen Shipu, such as Pukuashipu (Saint-Augustin) and Nataskuanshipu. The notion of borders is therefore a recent one imposed by Europeans and new Canadians.

The La Romaine reserve was officially created in 1956 following a complaint from a resident of La Romaine (P. A. Guillemette), who objected that in the summer Indigenous people’s dogs were destroying his gardens and their tents were encroaching on his land. During these years, the settling process began with the concentration of different families in Unamen Shipu, including the Marks from Coucoutchou. It also marked the permanent arrival of Oblate Father Joveneau and the Indian Residential School of Sept-Îles for the community’s youth. Living in houses and not tents was a difficult transition. The creation of beaver reserves by the federal government fragmented the forest territory by imposing a territory manager (tallyman), which limited access to the resource.